Your basket is currently empty!

Previously on How to License a Record

A small record shop opposite Iceland and BetFred took a step out of its comfort zone of selling records, RSD queues and dipped its toes into the strange new world of licensed reissues. One email to Universal Music, one deceptively simple PDF form, and suddenly I was in deep. Christmas came and went, then March, and still nothing. Then, finally, in June, came the news. The contract had been approved. The deal was real.

For the first time, Analogue October Records wasn’t just a name on a till receipt. It was an actual label. Catalogue… almost 1

The Contract

When the agreement landed, it felt monumental. Looking at my reaction, you’d have thought I had just joined the big league… but nothing could be further from the truth. At its most basic, I’m potentially just another reissue label, wanting to be seen (an heard). Big league? Well thats the preserve of Chad Kassem, MoFi etc etc Then there’s are the more established retailers… Chances of Mike from The In-groove holding up one of my releases in one of his weekly roundups of the weeks new releases? Slim…. Slim then, and sadly, still yet to happen.

Back to the contract… The terms were clear enough. Three years plus a six month sell off. I could press as many as I wanted within that window, but once the term ended, that was it. Anything left over could only be sold for six more months before the rights reverted. No secret warehouse sales. No “just a few boxes left.” It sounds brutal, but it’s tidy and fair.

The contract also granted worldwide rights, excluding North America.

It also required me to send them finished copies of the record. I loved that. Somewhere inside Universal, decades later, my release would be considered as part of the story, legitimate, sanctioned and hopefully, even an improvement!

No Master Tapes

The contract also covered the format the masters would be delivered in. I had asked for tapes, of course, but Universal explained that as a new licensee, tapes don’t really leave the vaults. They are assets, legacy items, and they stay put. I saw that not as a setback but as an opportunity. Do this right and maybe next time they would trust me with the reels. Regardless, I quite literally meditated on the digital question for a long time. More on this, below…

The Money Maze

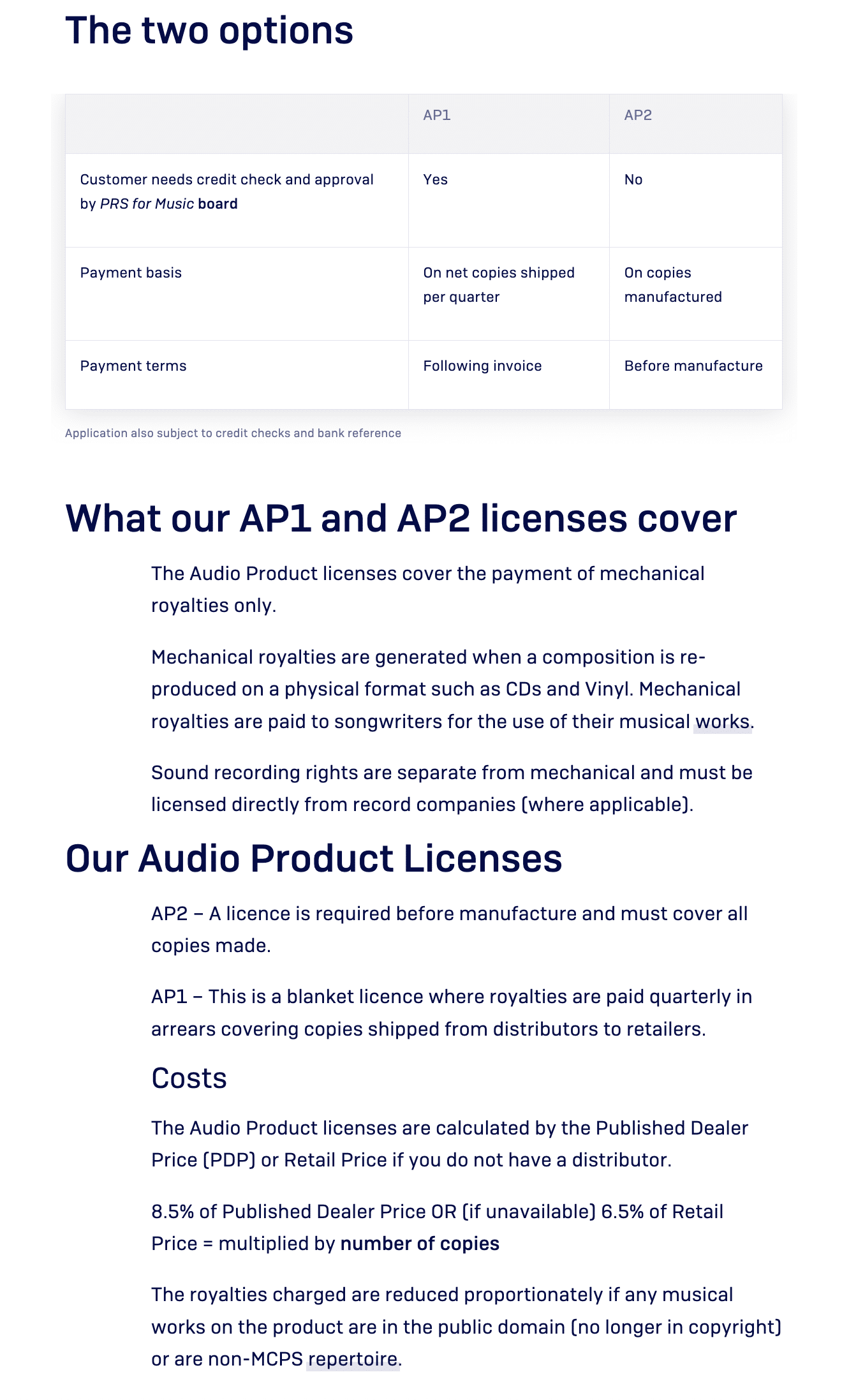

Then came the paperwork behind the paperwork, the label copy and the required MCPS Mechanical Rights.

MCPS, the Mechanical Copyright Protection Society, is the organisation that ensures songwriters and publishers get paid. Every record made has to account for the people who wrote the music, not just the ones who perform it.

Their system is beautifully logical. You declare how many records you plan to manufacture, and they invoice you before a single copy is pressed. The rate for vinyl is eight and a half percent of the dealer price, which is what you sell to distributors and retailers for. In my case that meant paying MCPS on one thousand copies up front, even though a few would inevitably end up in radio station bins or under someone’s coffee mug.

This is completely separate from the royalties owed under the licensing agreement itself. Those are paid on actual sales, and for this deal that rate was twenty five percent of the dealer price. Promos and review copies don’t count, because you haven’t sold them.

But you can’t go handing out hundreds of freebies either. Both the label and MCPS specify how many royalty free copies you’re allowed. In my case the cap was thirty. If I sent out fifty, I’d owe MCPS and Universal on the extra twenty. The system keeps everyone honest.

Then there’s the dealer price itself, the cornerstone of every calculation. You declare it, but it isn’t set in stone. If you tell Universal it’s eighteen pounds and later it creeps up, you have to let them know. Everything is adjustable. Transparency is key.

And this entire jungle of figures, royalties and percentages was being managed in Apple Numbers. It worked, but only just. NGL, it was utter chaos, a web of formulas that occasionally imploded under Apple’s quirky refusal to behave. But somehow, it held together.

The process itself is pretty straightforward. There are two options, AP1 and AP2, and you have to determine which applies to your planned release. Navigating the application on the PRS website is a breeze. But of course, it always bloody swings back to that damn question of the dealer price.

At this point, I decided it was time to rethink how I approach these projects. Maybe a Python based app that’s fed every possible cost, and then calculates not only the dealer price and royalties, but can also model projections for any route to retail, D2C, distribution, whatever*

But for now, on this first one, while I’m still finding my feet, I need to push on.

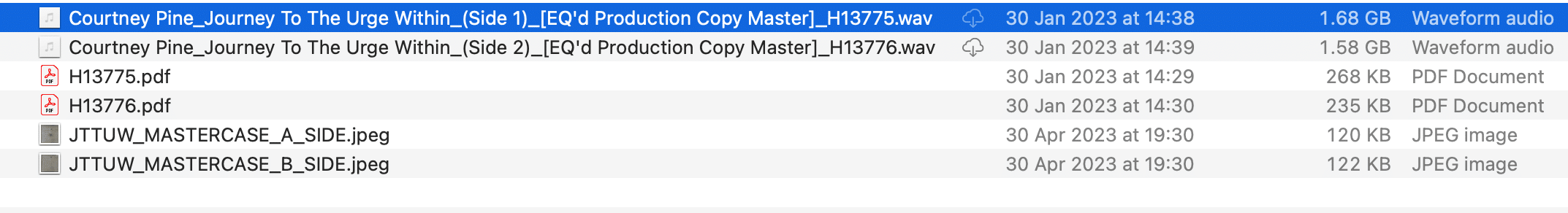

The Files

On the thirtieth of January 2023 I got an email from Universal with a link to their in house file transfer system. Two WAVs and a PDF scan of the original master tape boxes.

Not stock transfers. Fresh 192 24 transcriptions from the original masters, done at Abbey Road specifically for this reissue.

I know this record beyond well. I’ve heard it on every system imaginable. But when I hit play on those files through my reference setup at home, I heard things I’d never noticed before. Subtle layers. More breath in the sax, more space around the cymbals. It was like rediscovering an old friend.

The Plan

By mid April I had accepted that I wouldn’t be getting the tapes. Caspar from Gearbox rang me to talk about it. He was excited, not disappointed. He suggested recording the digital transfers back to tape on Gearbox’s Studer machines at fifteen inches per second. He said it would reintroduce the analogue warmth and dynamic feel, give the music that alive quality tape has that digital sometimes smooths away.

I’ll admit, I was sceptical until I tried it myself. I’ve got a few tape machines at home, Revox, Tascam, Teac. So I took some hi res files and recorded them back to tape. The difference was immediate. It wasn’t subtle either. It had weight, a kind of roundness that digital never quite nails. From that moment, I was in.

We would master from tape. No compromises.

But we also had to be transparent. When it came to marketing this release, I couldn’t say Mastered from the original analogue master tapes, because it wasn’t. The source was digital, a new 192/24 transfer from Abbey Road, and pretending otherwise would have been dishonest. I hate it when labels make those claims only for you to dig deeper and find a digital step tucked in the middle somewhere. Half speed mastering is the classic example. There’s nothing wrong with it, it can sound spectacular, but say so. Explain it. Don’t disguise it.

So I made a decision early on. Total honesty. If there’s a digital step in the chain, I’ll talk about it. I’ll explain why it’s there and what it brings to the process. In this case that high resolution transfer gave us a pristine foundation, and recording it back to tape on Gearbox’s Studer brought back the organic warmth and depth that digital can sometimes iron flat. The combination of both worlds, digital precision and analogue texture, made perfect sense.

When I had tried it myself at home on my Revox and Tascam machines, I had already heard the magic. The voodoo is real. Yes, there are some that may scoff at the idea, talking about generational loss etc.. There’s even one engineer who (on a live stream) just rolled his eyes… He is of course entitled to his opinion. But my opinion was that, as long as we remained transparent about the process and the reasoning behind it, and that IT SERVED THE MUSIC, it was more than just OK. It was amazing! The moment you roll tape at fifteen inches per second, something happens. The music breathes differently. It’s not nostalgia, it’s physics. And once I heard it, there was no going back.

Gearbox

The mastering session was on the thirtieth of June 2023 at Gearbox Records in London.

Caspar Sutton Jones is the real deal. I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again, he deserves to be mentioned in the same breath as Bernie Grundman and Kevin Gray. What makes Caspar special is that he doesn’t impose his sound, he collaborates with the record. He listens to it. He listens to you.

I had brought along a stack of reference pressings, UK, US and Japanese originals. We played them all. The UK was bright, the US the same. The Japanese pressing was rich, smooth and balanced but still had punch. Caspar asked which I preferred. I told him I wanted the chocolate smoothness of the Japanese cut with the sparkle of the UK. He nodded, grinned and got to work.

What followed was one of the most emotional moments I’ve had in this whole process. Hearing that record come to life after so long, after all the forms and invoices and waiting, was surreal. You’ll have to excuse me, but atthe time, I did well up… choked. All 6 foot 5 of me had to turn away and look at the wall whilst I regained my composure. This was quite the journey, and i’d never really given my self time to process the…. er… process (?). So when it finally hit me, it did so in the heart of Camden, mid mastering. Composure regained and lacquer finally cut, Caspar inscribed my dedication in the dead wax, a small secret mark of everything this project meant. The lacquers were boxed, sealed and shipped to Optimal.

And then came the waiting. Two weeks until the test pressings.

The Waiting Game & Side Quests…

Anyone who’s been through this will tell you that test pressings can go either way. Sometimes they’re great. Sometimes they’re not. They can be noisy, off centre, or pressed too cold. The first few discs off a new stamper are often made while the press is still coming up to temperature, and if you’re unlucky, those are the ones you get.

So the anticipation was real. This wasn’t about hearing Journey to the Urge Within for the first time in thirty years. I’d lived with that record most of my life. This was about hearing the result of every single decision made over the past two years. Every penny, every risk, every late night email. My money, my name, my neck, all on the line.

And it wasn’t just business. There were personal stakes too. Mrs C had her doubts, understandably. The world had long come out of a series of Lockdowns… , the economy was wobbly, and here I was sinking everything into a reissue jazz record. She worried it was a gamble too soon after the chaos. And in truth, she wasn’t wrong to worry.

But you can’t build something new without stepping off the safe path. The Australians have a quaint expression for this… If you know it, we’ll leave it there… if you dont, you’ll have to google it. It involves spiders and a few expletives. But it sums up my thoughts on this process perfectly.

So, with everything paid for (so far… a lot more more bills to come), the lacquers in transit and a whole lot riding on what came next, I waited.

Next time, the test pressings arrive. And I find out whether this whole adventure sings or wobbles.

*Regarding the App that I wanted to build….. I did. Its awesome…. I cant wait to show you what it can do.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

No responses yet