Your basket is currently empty!

Episode II: The Paperwork Awakens

Previously on How to License a Record for reissue

A tiny record shop opposite Iceland and BetFred somehow became a reissue label. There were mouldy tapes, sceptical band members, a global pandemic, and finally, one reckless email to Universal that somehow didn’t crash and burn. Then came The PDF… the mythical License Request Form, landing in my inbox like a message from the gods (or at least the Legal Department).

It was thrilling. Until I opened it.

Lessons learned from Episode I:

Enthusiasm is not a strategy. Channel it, don’t spray it. Emailing both the artist and the rights holder at the same time? Rookie move.

Digital isn’t death. That mouldy U-matic and the DAT copy taught me that a reissue’s quality comes from mastering, not mythology.

Survival first, then dreams. The pandemic reminded me that a label is only as strong as the shop and the film industry that funds it.

Patience is a virtue, but persistence is the superpower. That follow-up email, the one you’re nervous to send, might be the one that changes everything.

Listen, watch, and listen again. When you’re new to this and dealing with industry veterans, it pays to shut up and take notes. There’s experience in every raised eyebrow and every “hmm” that doesn’t make it into an email.

The Form

The License Request Form looks innocent enough. Just one page. A few tidy boxes. Some polite legal phrasing. Nothing to fear, right?

Except it’s probably the longest I’ve ever spent just looking at a single sheet of paper. Because that one page isn’t really a form, it’s a test. Every box hides a question you didn’t know you’d have to answer, and every term assumes you already speak fluent licensing. It’s like opening a crossword written by lawyers for other lawyers, with the occasional trapdoor labelled “Dealer Price.”

As a record shop owner, I know exactly what a dealer price is. But arriving at one? That’s a different beast. To know what I could sell it for, I first had to know what it would cost to make, and to know that, I had to know what I’d make from selling it. It’s circular logic at its finest. I stumbled at the first hurdle.

Then came Royalty Rate. I get royalties; I still get the odd cheque whenever an old clip of Rainbow pops up somewhere (long story, IYKYK). But how are royalties calculated? Retail? Dealer? Turns out, they’re based on the dealer price, what the shop pays, not what the customer does. Makes sense in hindsight, but at the time it felt like discovering gravity mid-fall.

Next came Advance. And here, I confess, I was guessing. There’s no manual for this kind of thing, no “Licensing 101.” This was before you could just say, “Hey ChatGPT, what does this mean?” So I worked it out: not a fee, but an advance against royalties, recouped later. Still, four or five questions in, I was already sweating through my T-shirt.

Term was easy enough, three years with a six-month sell-off period. Except, wait… sell off what? Cue frantic Googling. Turns out, you can press as many copies as you like within that three-year term, but once it expires, you can’t make any more. You get six months to sell whatever’s left, and after that, anything still in boxes has to be destroyed. Yes, destroyed. Perfectly good vinyl, gone. Somewhere, a million voices suddenly cried out in terror….

Then came Territory. Simple. Worldwide. Because if you tick “UK only,” you have to recalibrate everything: pressing quantities, manufacturing costs, dealer price. It’s all interconnected. Worldwide was the only choice that made sense, but also the one that quietly implied you’d now be handling royalties, accounting, and reporting on a global scale. Gulp.

Then the only field that didn’t make me sweat: Label of Release and Contracting Party. Analogue October Records for the label, my limited company as the contracting party. Finally, a box I could tick without imposter syndrome.

Distribution, though…that one caught me again. Sell it myself or go through a distributor? At that point, I decided to give it a go on my own. I needed to understand how distribution actually worked. I knew a few people…Luther, the rep of all reps from Universal, and the team at Gearbox Records. I figured between them, I might just survive the learning curve.

The next question…Original Release Label and Date, was mercifully easy: Island, 1986. And Number of Tracks? Ten. Estimated Sales? That one was less of a calculation and more of a séance. Time to channel Mystic Meg (a TV fortune teller from back in the day). I saw sales. Lots of them. If you build it, they will come. A thousand copies felt right. In hindsight, 750 would’ve been wiser, but hindsight wasn’t at the table.

Finally, Track Listing and Other Info. Easy peasy, lemon squeezy. Until I got to that last line. What else was there to say? Then it hit me: I can’t be called Analogue October Records and have my first release sourced from digital. So I wrote, “Prefer to master and cut from the original analogue master tapes.” Pure, blind optimism. Of course they’d let me cut from tape. Right? Spoiler: no.

The Network

I finally hit send. The form vanished into Universal’s licensing ether. I half-expected a bounce-back saying “Cute.”

But while I was wrestling with that page, three people became my lifeline. Andy, a local friend who did shifts at the shop between his day job as, miracle of miracles, a reissue consultant for Universal. Luther, the rep of all reps, also from Universal, who helped me make sense of the distribution puzzle. And the team at Gearbox—Caspar Sutton-Jones and Darryl, the owner… who welcomed me into their London HQ like family.

I’d gone there just to buy some stock and have a look around. Within minutes we were deep into mastering chains, pressing plants, and the art of cutting. It just seemed right to ask, “If this actually happens, could you master it here, and maybe handle the pressing at Optimal?” Without hesitation: “Yes, of course, we’d love to.”

No corporate gatekeeping, no polite deflection, just genuine enthusiasm. Between Andy’s inside knowledge, Luther’s steady guidance, and Gearbox’s generosity, the fog started to lift. I was beginning to understand the shape of what I’d taken on.

The Wait

And then… silence.

The wait was brutal. But I need to say this upfront: the slow nature of the process should never reflect poorly on the licensor. There are so many moving parts. Beyond the catalogue meetings every other Thursday, they have to get clearances from Legal, check the original 1980s contracts, ask Iron Mountain to dig out the tapes, and get feedback from the artist or their estate. Every one of those steps takes time, and rightly so.

Speaking of Iron Mountain, you may be wondering what that is? Well, its a company that literally specialise in super safe and secure storage for archives etc. If you have the time, this video by Michael Fremmer is a great look at one particular Iron Mountain facility (which actually IS inside a mountain)

Anyway, back on topic… like I said, theres a lot of moving parts, so its not really a delay, it’s due diligence. Licensing is archaeology with paperwork. And now seems like the best time to give props to Anthony at Universal / Licensing… He kept me updated and informed at every single development.

Still, it dragged. Andy and Luther kept me sane, explaining the internal process: how requests are weighed up, which titles are already licensed, how some projects might get bumped because of demand, or even, so I’m told, the mean selling price on Discogs. If something’s fetching hundreds and thousands are on the wantlist, the catalogue team might choose to reissue it themselves..and fair enough.

But knowing the logic doesn’t make the waiting any easier. (Note: This isnt unique to me… its par for the course. Its now a part of the process I am able to work with and navigate. But at the time, with it all being so new, and with a vertical learning curve, it takes time to get your head around all the finer details of the process. HINT: take notes… they come in handy!)

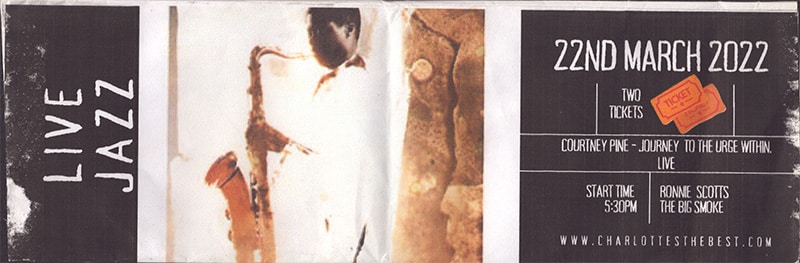

Christmas Day 2021

The first “somewhat normal” Christmas that didnt require face masks or distancing! The family’s gathered. Charlotte( my eldest and the shop’s manager) hands me a folded sheet of paper. “strange gift” was my first initial thought… At first glance it looks like a concert ticket: Courtney Pine – Live at Ronnie Scott’s. My heart skips a beat.

It’s a mock-up she’s made, the real tickets on their way. I’ll be seeing Courtney live, performing the very album I’m hoping to license, as a celebration of its anniversary (but postponed due to YOU KNOW WHAT).

Surely by March it’ll all be rolling. The form’s been sent, the gears are turning—by then we’ll be knee-deep in test pressings & artwork? Right?

March 22, 2022

Ronnie Scott’s. Charlotte beside me, the obvious choice for my second ticket. The lights drop, the band walks on, and Courtney brings the heat. The set is electric. The man hasn’t lost a step. I’m sat there, equal parts pride and panic, thinking, “Still no license.” Its coming…. I can feel it…. a matter of days….

It would be 21 June 2022 before it was finally agreed and executed. Do the math.

That six-month stretch wasn’t wasted, though. Somewhere in that limbo, Universal sent me something so unexpectedly brilliant that it reignited everything. Something that changed the project’s trajectory completely.

But that’s for next time.

Stay tuned. Episode III is where things really start to move, and the real work begins.

Comments are closed