Your basket is currently empty!

If you’ve spent any time digging into the undercurrents of British jazz, the name Henry Lowther will already be carved in your consciousness. Trumpeter, flugelhorn player, composer, bandleader… his sound has graced stages and studios for over six decades. But for every fiery solo with the London Jazz Orchestra, there’s also the quieter truth: you’ve probably heard Henry without even realising it, through the grooves of countless pop and rock records.

Lowther is one of those rare figures who moves seamlessly between the worlds of improvised jazz invention and mainstream session wizardry, bringing the same integrity and creativity to both.

The Jazz Years: Still Waters Run Deep

While casual listeners might discover Lowther via an Elton John or Nick Drake record, his heart has always beat for jazz. He was there during the heady days of the late 1960s British jazz renaissance, performing with the Mike Westbrook Orchestra, John Surman, and of course the visionary Neil Ardley, whose large-scale works blurred the lines between jazz, classical, and the avant-garde

Lowther’s own group, Still Waters, became a vital expression of his musical personality: lyrical, questioning, and exploratory. And his role within the London Jazz Orchestra (LJO) has cemented him as not just a player but an elder statesman of British big-band jazz, still shaping its sound well into the 21st century.

It’s worth pausing on Neil Ardley here: Ardley’s daring compositions often required musicians who could think beyond genre, who could fuse precision with freedom. Lowther was the perfect foil. Their collaborations were a testament to how British jazz could be as ambitious and boundary-pushing as anything coming out of New York.

And then there’s Barbara Thompson… another giant of the scene whose bands were both powerful and progressive. Lowther played in her Latin-infused project Jubiaba, a group that married jazz to rock and Afro-Cuban rhythms. His presence in those circles speaks volumes: he was trusted by the very best, the musicians who were breaking ground and rewriting what jazz could be in Britain.

The Pop Sessions: Unsung Hero of the Studio

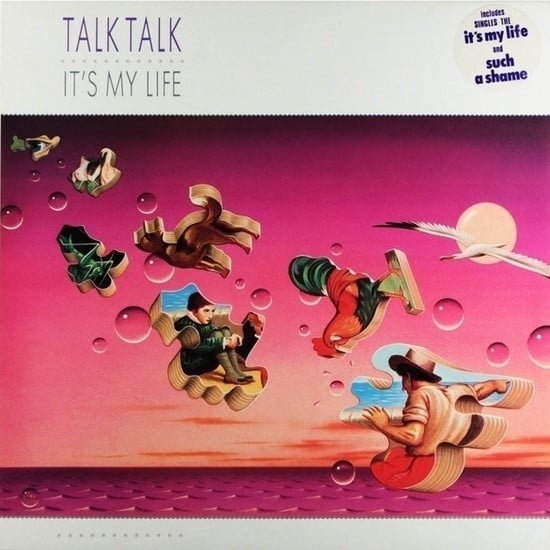

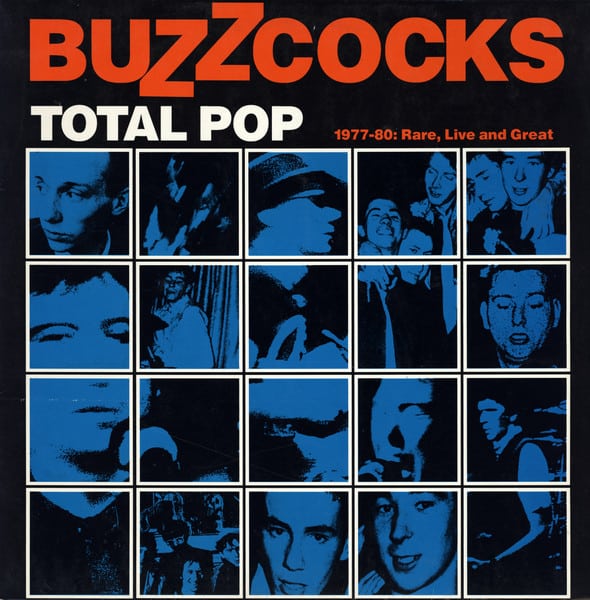

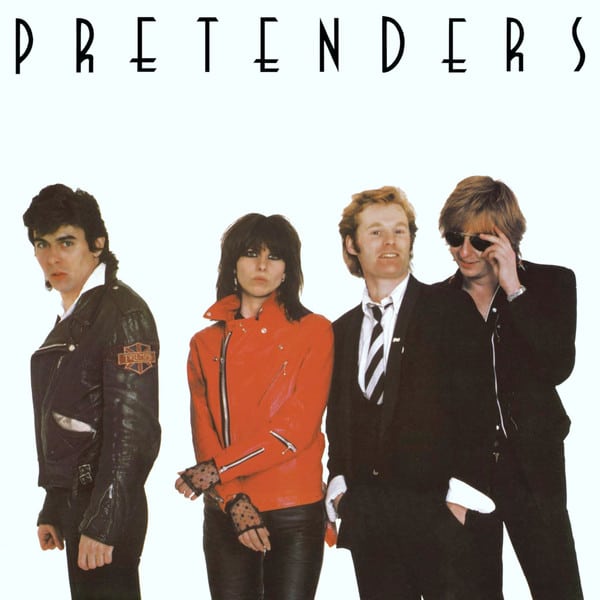

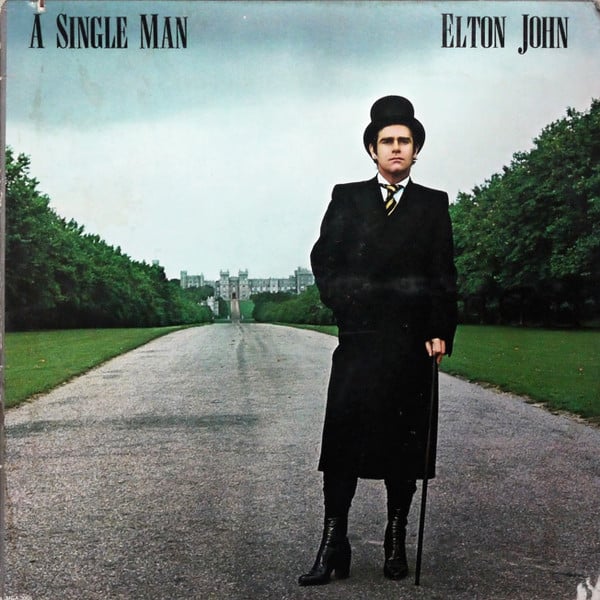

Yet, while his jazz peers knew him as a fearless improviser, the pop world knew him as a consummate professional. Lowther’s horn is threaded through the fabric of British popular music. His credits range from Manfred Mann and the Keef Hartley Band (with whom he played Woodstock in 1969) to records by Elton John (Tumbleweed Connection) and Nick Drake (Bryter Layter).

Session musicians rarely get their names in lights, but they leave fingerprints everywhere. Lowther’s adaptability… the ability to switch from a biting jazz solo to a perfectly polished studio line… is why producers kept calling him back. He had the chops, but more importantly, he had the musicality to serve the song, whether it was destined for Ronnie Scott’s or Top of the Pops.

Bridging Two Worlds

It’s this dual legacy… the jazz innovator and the session stalwart… that makes Henry Lowther such a compelling figure. Few players have contributed as much to both sides of Britain’s musical coin. He embodies a period when boundaries blurred, when jazz musicians brought sophistication to rock, and rock gave new audiences to jazz.

Listen to him with Still Waters, and you’ll hear the searching spirit. Drop the needle on a classic pop record, and you’ll hear the same horn that once soared over Ardley’s epic charts. Lowther connects these worlds, and in doing so, he represents the very best of British music’s cross-pollination.

Looking Ahead: 85 and Still Composing, Still Exploring

And here’s the thing: Henry Lowther is not done yet. In 2026, he turns 85… a milestone we’ll celebrate with a special release featuring his original compositions for the London Jazz Orchestra. It’s not about a spotlight trumpet showcase (though there are a couple of solos to savour). It’s about Henry’s voice as a composer, expressed through the colours, textures, and energy of the orchestra he has helped shape for decades.

The album will be called Primetime, and personally, I can’t think of a better name.

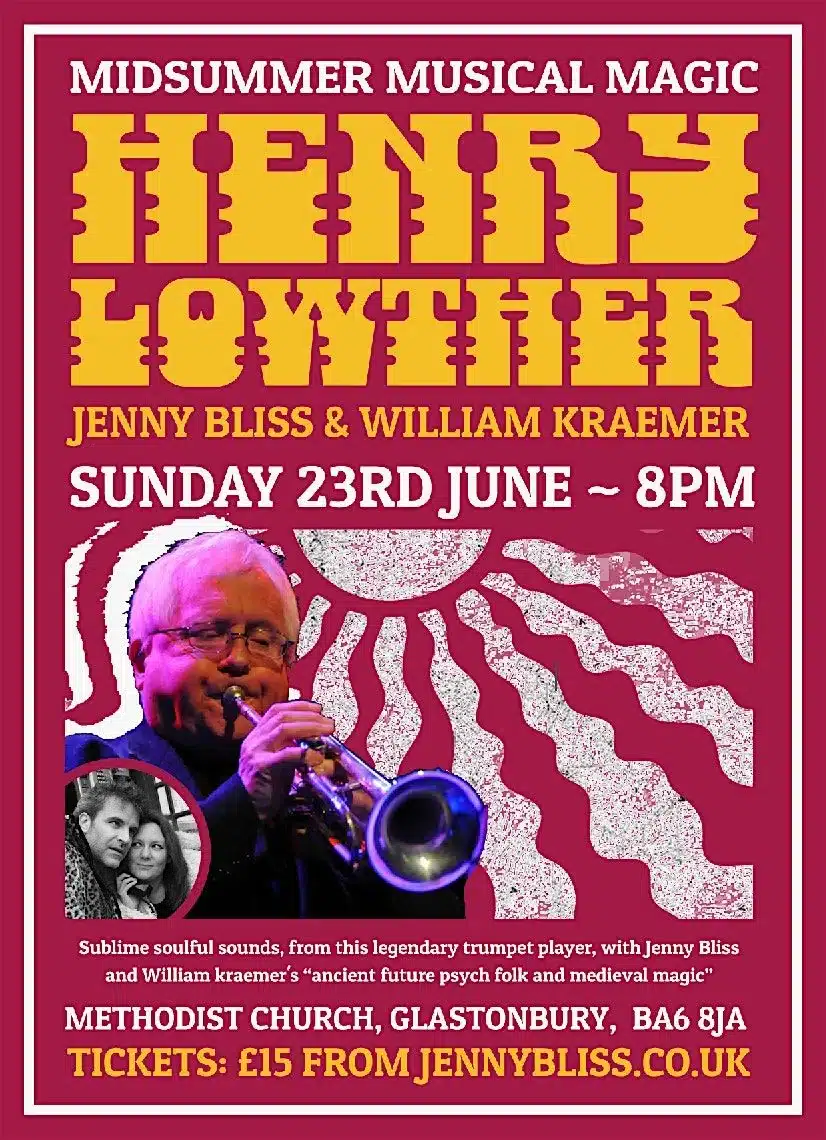

Now… if you think Henry is only looking backwards, think again. Fifty-six years after playing Woodstock, he made his Glastonbury debut in 2024… at 84 years of age… with Queen Space Baroque, a quartet led by the extraordinary violinist Jenny Bliss. It’s a bold new direction, proof that Lowther is still seeking out fresh horizons, new collaborators, and uncharted sounds.

85 is the New Sixty

In a meeting today, Henry and I joked that 85 is the new sixty. He didn’t flinch… for him, age is just a number. It’s the music that matters.

If Neil Ardley was the composer’s composer, then Henry Lowther is surely the musician’s musician. Chances are, he’s been part of your musical journey without you even realising it.

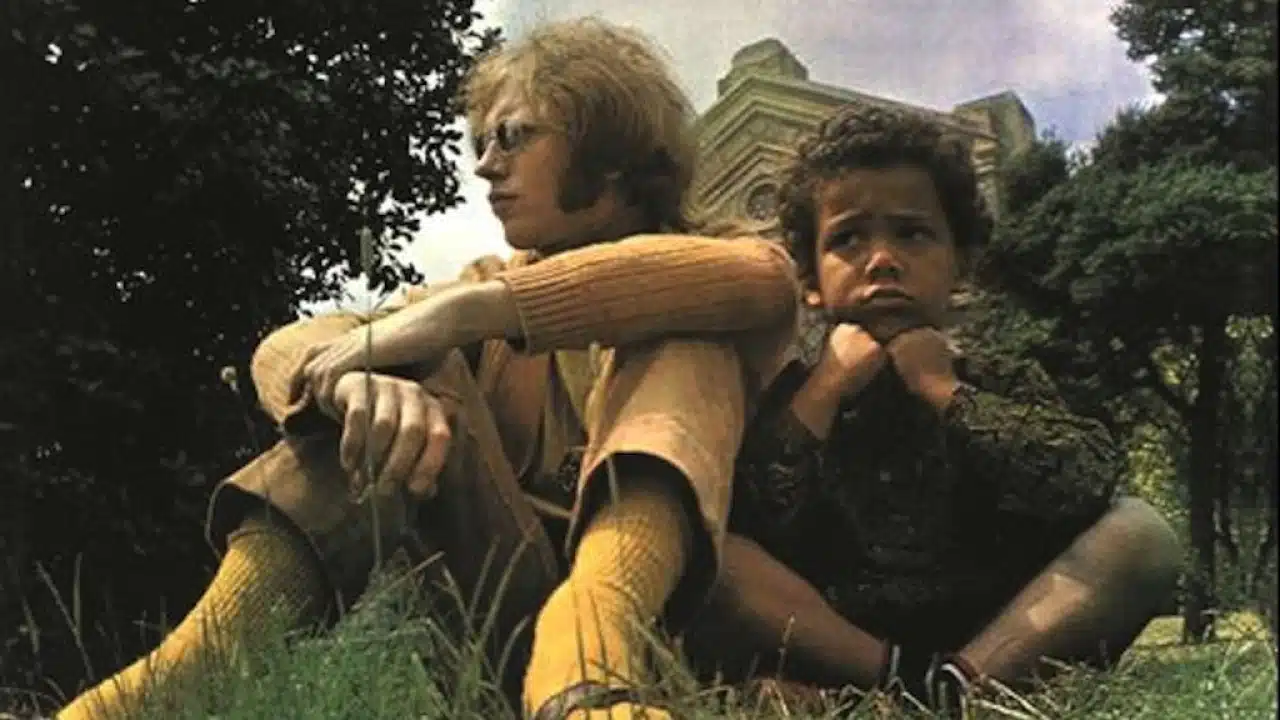

One of my favourite albums of his, Child Song, happens to be as old as I am. On repeated listens recently, it’s clear the record has aged far better than I could hope to. The music still feels organic and alive… the lines bob, weave, and grow through time. They adapt not only to the era they were recorded in but to the ears of a modern-day listener, recalibrating themselves with uncanny freshness.

It’s a rare talent, reserved for artists of a certain stature: Ardley, Barbara Thompson, Ian Carr, Nucleus, Gil Evans, David Axelrod, and everyone’s favourite musical chameleon, Miles Davis. Henry belongs in that company.

And that’s why I can’t wait to share what we have planned between Henry, the LJO, and Analogue October Records. Stay tuned… it will be special.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

No responses yet